Yoga, Environment and Language

“Yoga is not just about exercise; it is a way to discover the sense of oneness with yourself, the world and the nature.”

With this statement, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, proposed establishing an International Day of Yoga. The aim is to raise awareness for the benefits of the ancient practice for our modern times. His proposal was accepted by an overwhelming majority of 175 member states of the United Nations. On 11 December 2014, the General Assembly declared 21 June International Yoga Day. In large parts of India, the day enjoys a great deal approval and is understood as a reclamation of Indian culture. However, there are also many critical voices raised against this day. Narendra Modi is considered a Hindu-nationalist politician who violently attacks other cultures and religions in India, which is in no way compatible with the philosophy of yoga.

The day is celebrated in India and the Global North, where numerous events take place to mark World Yoga Day. But there is an urgent need to distinguish how yoga is perceived in the Global North in contrast to India. The physical practice is at the centre of this perception, usually limited to asanas (body exercises). The philosophy of yoga plays a subordinate role.

The number of yoga practitioners worldwide is around 300 million, and the yoga industry’s turnover is estimated at approximately 130 billion US dollars. As of 2016, there are 300 yoga studios in Berlin alone. In addition to yoga and meditation classes, the yoga market consists of teacher trainings, workshops and festivals offering various other products such as yoga mats, accessories like blocks, straps and meditation cushions, or yoga clothing. The share of the yoga market for clothing alone is expected to reach 48 billion US dollars in 2025. However, products that are only remotely related to yoga are also advertised. This includes natural cosmetics, essential oils and jewelery. Yoga has become an industry from which the Global North profits, so we can clearly speak of cultural appropriation – a culture, mainly of the colonised, is taken out of context and adapted, often with financial gain for the Global North.

How do consumerism and language belong together?

In his book Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology and the Stories We Live By, linguist Arran Stibbe describes the connection between language and the environment, specifically as manifested in language use. He introduces widespread narratives, such as the centrality of humans, or that humanity is oriented towards the belief that increasing ownership is good. This has a lasting influence on thinking, speaking and acting, and Stibbe argues that new narratives are needed. In the various chapters of his book, he names nine narrative instruments, and shows how they manifest in language use. One of these tools is ideologies shaped by discourses, which he classifies as destructive, ambivalent and beneficial. According to Stibbe, a beneficial discourse would be a narrative that influences our behaviour in such a way that nature is actively protected. In this context, Stibbe points out that in many indigenous communities nature is viewed with more appreciation and can be an important source of new narratives. However, finding inspiration in other cultures always carries the danger of alienating and incorporating them into capitalism – as in the case of yoga. Especially when promoting yoga and the supposedly associated products, it is easy to see how far the Global North has moved away from the tradition.

The Philosophy of Yoga

But what is yoga, actually? If the term yoga is translated from Sanskrit, it stands for unity. In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra (interpretation by Desikachar 1997), yoga is defined acenters a state where mental processes come to rest. As a result of this state, practitioner acquires the ability to “…realise something fully and correctly.” The goal of the practice is to achieve oneness with the self and all other living things. If actions are not directed towards this goal, they cannot be called yoga.

The Yoga Sutra describes a non-linear eightfold path (ashtanga) to be followed on the way to the goal of yoga. The eightfold path consists of:

1. yamas (attitude towards our environment and surroundings)

2. niyamas (attitude towards ourselves)

3. asana (physical exercises)

4. pranayama (breathing exercises)

5. pratyahara (mastery of the senses)

6. dharana (concentration)

7. dhyana (meditation)

8. samadhi (state of consciousness in which discursive thinking ceases; oneness)

The yamas, in particular, are important, as their content overlaps with what Stibbe calls eco in Ecolinguistics – a sustainable interaction with the environment and others. Accordingly, yoga can be seen as an ecological way of thinking, particularly evident in the five further points into which the yamas are divided, essential for harmonious interaction with the environment and other people. The yamas are:

1. ahimsa (non-violence)

2. satya (truthfulness)

3. asteya (non-stealing and non-desiring)

4. brahmacharya (moderation)

5. aparighara (non-possession)

Ahimsa (non-violence) refers to non-violent interaction in direct contact with other people and means that no suffering should occur for others. This includes animals, careful use of natural resources and questioning the consequences of our consumption for other parts of the world and the people living there. Satya (truthfulness) should be considered in the context of ahimsa and describes sincere communication through speech and actions. Asteya (non-stealing, non-desiring) can refer to actual theft but mainly includes the ability to let go of things or of the desire for items that do not belong to us. This definition can be expanded to include the privileges granted to communities of non-marginalised groups. Brahmacharya is often translated as abstinence, which can be a form of moderation. Still, it generally implies a certain restraint in all actions, for all areas of life, be it avoiding excessive eating, too much work, or excessive consumerism. The fifth and final point of the yamas is aparighara (non-possession), which in traditional practice can be interpreted as detachment from all worldly possessions. Still, it describes the ability to take only what is really needed and deserved.

The philosophy of yoga can be viewed as a beneficial discourse, which Stibbe describes as a discourse that conveys ideologies that can actively encourage people to protect the foundations of life. According to Susanna Barkataki, yoga teacher and activist, if life is aligned with the yoga philosophy, meaning the goal of creating unity, there is no way around activism. This applies to discrimination, social injustice or climate change. It automatically results in a more conscious and sustainable lifestyle and consequently contributes to the protection of nature.

Linguistic Patterns in Yoga Advertising: Framing – Identity – Evaluation

As a linguist and yoga practitioner, I find it very interesting to look at yoga, especially product advertising, from a linguistic perspective and ask how it aligns with the philosophy of yoga.

Framing

Framing is a common linguistic practice we encounter daily in the media. Knowledge about one area of life is used to describe another with the help of trigger words. In descriptions of products, the frame YOGA IS WELLNESS is used. The Digital Dictionary of the German Language defines wellness as “… physical and mental well-being to be achieved through (therapeutic) treatments, conscious nutrition, beneficial body care, appropriate physical activity or similar (as part of a holistic health concept).” This reduces the complex philosophy of yoga to a self-care practice. Trigger words such as mindfulness, well-being, intention and balance arouse associations that evoke beliefs and action patterns related to wellness, which are then equated with yoga. Even though personal well-being is part of the philosophy of yoga, described in more detail in the Niyamas (attitudes towards ourselves), the frame YOGA IS WELLNESS limits the practice to this aspect alone and excludes the social and ecological focus of yoga philosophy.

Advertised products are meant to support self-care or are tools of self-care. This can encourage consumption or, even further, to self-care being linked to consumerism.

Identity

From an Ecolinguistic perspective, identity means a narrative about a person or group of people expected to be embodied in a particular context. This includes value systems, appearance and behaviour. Similar to framing, it is triggered by words that create an association with certain personality aspects related to yoga practitioners. These include the terms sustainable, mindful and conscious, which are repeatedly found in advertisements for yoga products. The construction of an identity around yoga is used to make promises of becoming that person when the products are consumed.

Evaluation

Evaluations portray areas of life as positive or negative, expressed linguistically through appraisal patterns. These appraisal patterns reflect the values of a community. Opposing word pairs are a standard appraisal device, triggering positive and negative evaluations. In the yoga community, the appraisal items healthy, sustainable and natural stand out and are easily associated with the negatively connotated term: healthy/sick, sustainable/wasteful and natural/artificial. This results in the evaluations SUSTAINABLE IS GOOD, HEALTHY IS GOOD, and NATURAL IS GOOD, which are used repeatedly to describe products. This produces the belief that products can be consumed safely, and that certain products must actually be consumed to lead a sustainable, healthy lifestyley.

All three points are in opposition to the yamas brahmacharya (moderation), aparighara (non-possession) and, depending on the production, composition and necessity of the products, ahimsa (non-violence). But satya (truthfulness) also plays a role since the question arises of how excessive consumption is compatible with the identity of a yoga practitioner.

And then there is the question if this is still a beneficial discourse, as the yoga philosophy suggests. A market has been created from the indigenous tradition of yoga, which shows the great danger of appropriating cultures, falsifying them and embedding them in capitalism. Has yoga, as it is widely practised in the Global North, become a destructive discourse? Even if the products are sustainable and fewer resources are wasted, which is often not the case, the goal is to encourage yoga practitioners to consume. And this is justified by a narrative that the yoga practice can be carried out better, the lifestyle becomes healthier and more sustainable, or that people become a real yogi*ni if only the right products are consumed.

For me, yoga is a moral compass, and I always ask myself: Is this still yoga that I am practising right now? Unfortunately, I can’t always answer yes to that question, but it offers me guidance on where I want to go.

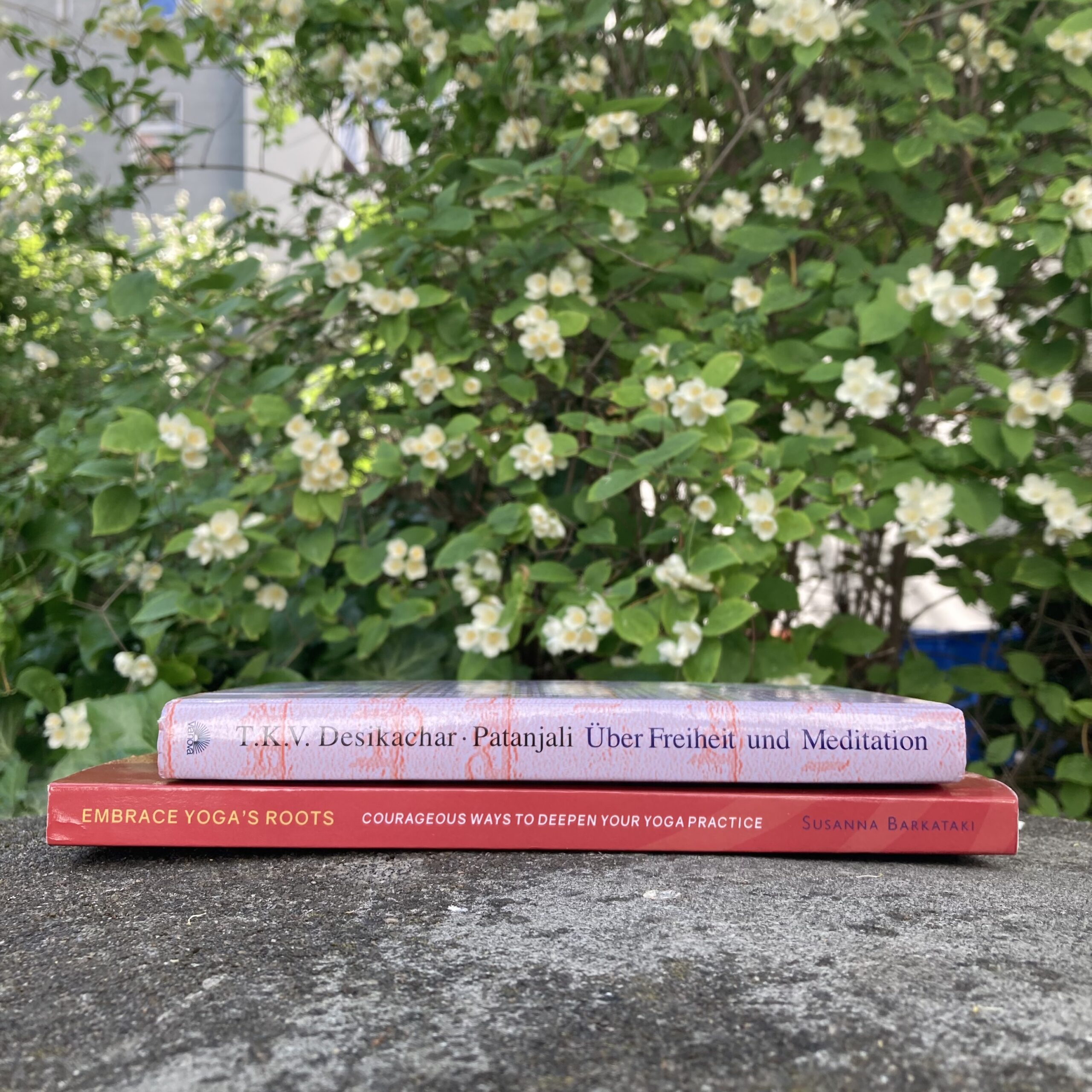

These books and podcasts have helped me on this path so far:

Yoga is Dead: Podcast by Tejal Patel and Jesal Parikh

Susanna Barkataki’s book Embrace Yoga’s Roots

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali as interpreted by T.K.V. Desikachar