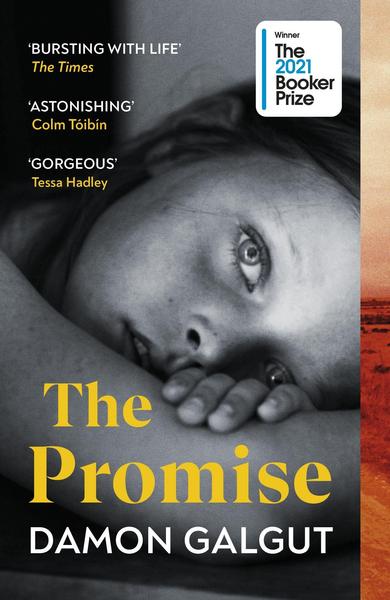

The Promise

Formally, this is the most interesting and surprising book I’ve read in a while – and it is its formal innovation that the jury of the Booker Prize praised in particular when they made Damon Galgut’s The Promise the winner of the award for 2021. The novel is structured around the four funerals of different members of the Swart family, a white South African farming family, and spans different epochs in the history of the country in which it is set: from the anti-apartheid civil unrest of the 1980s, to the turn to democracy in the 90s, through the AIDS-denialism of former president Thabo Mbeki, the corrosive corruption of the Jacob Zuma presidency, and on up to the Cape Town water crisis of the late 2010s. Galgut expertly pins his narrative to this backdrop, but always stays close – often uncomfortably close while still somehow holding them at a distance – to the painful particularities of the characters that make up the family.

The novel pivots around a promise made by the father to his dying wife. He promises to give to Salome, the domestic worker who cares for the mother through the illness that kills her, the house on the farm property in which she lives. This promise is heard by the youngest of the Swart children, Amor. But upon her mother’s death – you guessed it – the man keeps no such promise, indeed claims to have no recollection of having made it. So unfolds with what feels like dooming inevitability the passing of one family member after another without the fulfilment of the promise made. The allegorical resonances are almost too obvious to articulate: the charting of the failure of the white family to give to the Black woman what should be hers. Galgut’s narrative to some extent also denies the simplicity of this being anything like the ‘correct’ thing, or a ‘solution’ of any clearcut kind, when he not only has Salome’s son Lukas rejecting the notion of their house as a gift any of the Swarts have the right to give; as well as by including mention of a land restitution claim that has been lodged by a community that lived on the farmland prior to the Swarts coming into ‘ownership’ of it under the auspices of colonial and/or apartheid-given structures. In short, it’s complicated, and to a great extent, Galgut’s novel doesn’t try to make any of it uncomplicated.

The novel’s narration is free-floating: it moves from character to passing character, sometimes within a single sentence, adopting their ‘I’, their eyes, their idiom – sometimes whimsically following them for a short jaunt and then chastising itself for getting distracted. It is a narrative voice that is both one and many, intimate and always at enough of a distance to judge itself and its object, mostly sardonically. It has a dark sense of humour. It is scathing in its handling of all of its religious representatives, as it is of the white South African ‘types’ it almost caricatures in figures like the dreadful Tannie Marina (explicitly racist and a sadist) or the unbearable Desirée (privileged daughter to an apartheid bigwig who confessed crimes to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission).

The Promise marks the third time a South African writer has won the Booker: Galgut joins fellow laureates Nadine Gordimer and JM Coetzee. The book is executed with a real skill for the craft of writing, and commands respect for the author’s handling of his medium. At the same time, the novel and its lauding with this prize nonetheless do seem to confirm for me suspicions I’ve long had that there is a certain kind of story, or a certain kind of book about South Africa that seems to appeal to international audiences and international awards panels. It’s written from a certain vantage point, and it handles that vantage point with skill. Nonetheless, I wait impatiently for such highly visible awards to go to some of the deserving writers of colour in the country.

Order the book here and support us! The work behind poco.lit. is done by us – Anna und Lucy. If you’d like to order this book and want to support us at the same time, you can do so from here and we will get a small commission – but the price you pay will be unaffected.