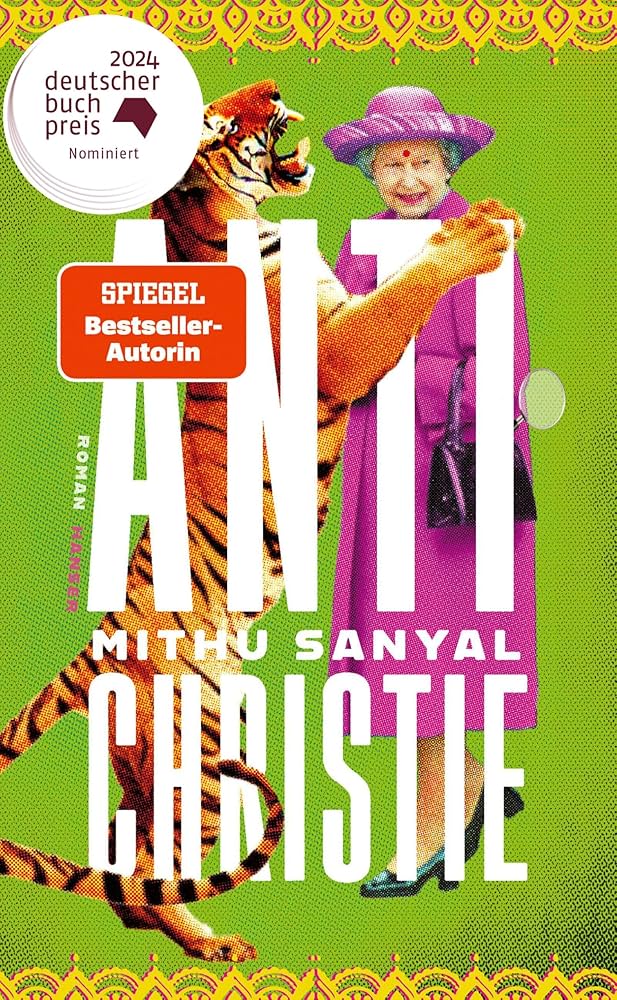

Antichristie

The only resemblance that Mithu Sanyal’s second novel Antichristie (as yet no English translation) bares to its predecessor Identitti is that both the story and its narrative style are a wild ride. The 50-year-old protagonist Durga lives in Cologne and her mother has recently passed away, but despite her grief she travels to London for a job. Durga is part of a writer’s room tasked with creating a new Agatha Christie film adaptation – those involved think it’s coming at the right time, but numerous protesters criticise the leaked plans as being “woke”. As if that weren’t enough, Durga suddenly travels back through time. To her own surprise, she lands in the year 1906, is now called Sanjeev and is fascinated to discover that she has a penis – an addition which seems typical of Sanyal’s humour.

I rarely voluntarily choose to read stories about time travel, even though when done well they not only create narrative potential, but also orchestrate and scrutinize connections between the past and present. And this is exactly what Sanyal accomplishes with Antichristie. At the start of the 20th century, in the middle of London and in the heart of the Empire, Indian students worth remembering lived in Shyamji Krishna Varma’s India House, including the revolutionary and anti-colonialist Madan Lal Dhingra or the controversial (to put it mildly) Vinayak Savarkar, who later became a visionary of radical Hindu nationalism. Durga lives as Sanjeev for several years together with these men – all of whom are historical figures – conducting extensive political discussions that were extremely important for the Indian fight against colonialism, but which through (Durga’s) contemporary perspective often seem problematic – nationalism was an important key word (as in many anticolonial movements) and feminism was relatively unknown. Mohandas Ghandi comes to visit multiple times, and although Durga has always admired him, as Sanjeev she learns that Ghandi, too, was not always faultless. Overall, this part of the story imitates the form of a crime novel in some aspects: in India House, an (alleged) locked-room murder mystery takes place which has to be solved, and who would be more fitting to take on the task than Sherlock Holmes? He often expresses himself in a condescending through to downright racist manner towards Indians, but he helps Sanjeev anyway.

The work in the writer’s room continues pushing forward and Sanjeev’s experiences steer some of Durga’s google searches in useful directions. The group almost endlessly discusses the relationship between Hindus and Muslims in India, facilitates conversations with those who protest against their work and teases Durga about her double episode for the British cult series Dr. Who being only counted as one. Sometimes I got a little bit lost in the dialogues. Throughout this, Durga is repeatedly haunted by the grief for her eccentric mother. It was not her Bengali father Dinesh, but her white German mother Lila who, during her childhood, constantly shared historical facts about the Indian resistance against colonialism with her. This brings me to another enjoyable layer of Sanyal’s novel: Durga’s family and friends. All of the characters are lovingly developed and their relationships to each-other are equally as complicated as they are human. So, the novel has much to offer and I am grateful for Sanyal’s enriching voice in German literature.

Order the book here and support us! The work behind poco.lit. is done by us – Anna und Lucy. If you’d like to order this book and want to support us at the same time, you can do so from here and we will get a small commission – but the price you pay will be unaffected.