What does ‘postcolonial’ mean?

poco.lit. is a platform for postcolonial literatures – but what does that actually mean? Postcolonialism developed as a field of academic enquiry that has been gaining visibility since the 1970s – one of the earliest and most well-known works of postcolonial scholarship is Edward Said’s Orientalism, published in 1978. This was an early, influential contribution to a field of study that critically questions colonial modes of representation. A further important aspect of postcolonial study is to draw out forms of resistance to these colonial practices.

Postcolonial literatures provide us with imaginative projections of the world that interrogate existing, colonially determined power relations. One early, significant form this took was articulated by Bill Ashcroft, Helen Tiffin and Gareth Griffith in their 1989 book as The Empire Writes Back (it’s a play on Star Wars) to describe when the colonised ‘wrote back’ at colonial representation. This was an empowering move on the part of the colonised to appropriate the language and forms that colonialism had violently imposed on them, and assert their ability to represent themselves and tell their own stories.

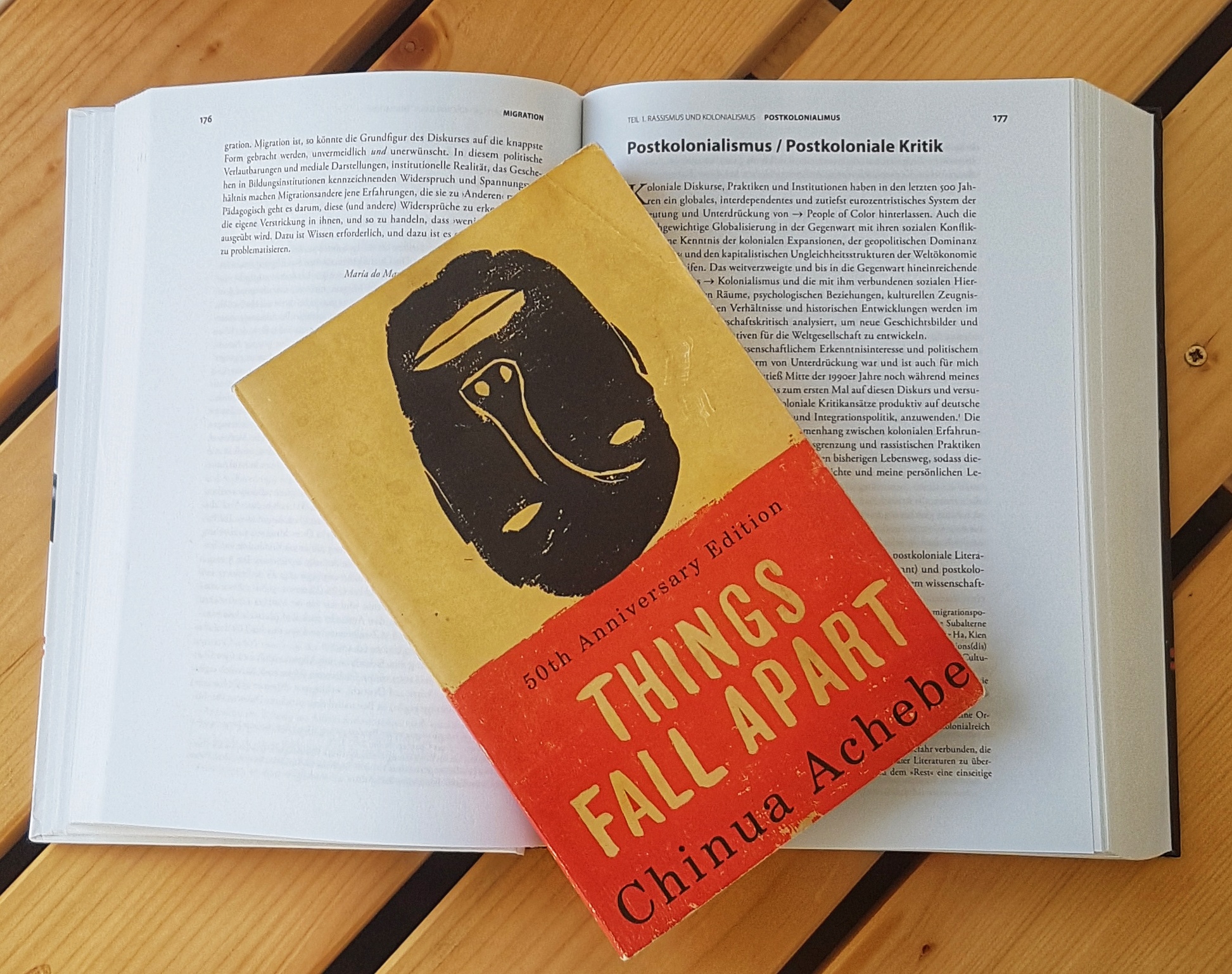

The novel Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, for example, writes back to the British classic Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. Rhys’ novel is a postcolonial Gothic tale concerned with the dark underside of Bronte’swork, which makes the maligned and marginalised figure of Bertha Mason – the novel’s famed mad woman in the attic – its central character, as it traces her early life in the Caribbean. It tells the story that Bronte’s work leaves invisible. Another example would be Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which writes back at stories of colonial encounter in Africa from the perspective of racist Europeans, like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, to emphasise the complex modes of resistance practiced by the communities being colonised. It reinscribes the colonised’s agency and their precolonial history. One could also think of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, which depicts India’s independence from British rule and the partition of India and Pakistan, and incorporates magical realism and an ironic interweaving of the literary-cultural imports inflicted by colonialism. This book complicated the idea of the postcolonial Indian novel in English as a mere offshoot of English literature proper.

The prefix post in postcolonialism suggests that the term could be read as a temporal marker: that it refers to a time after colonialism. But this is an understanding that many – and we at poco.lit. count ourselves among them – would reject, because colonial relations still very much exist, and continue to structure inequalities, real and representational. To interpret postcolonial as suggesting that coloniality is over rides roughshod over the many ways in which it clearly isn’t. For these reasons, we prefer to read the postcolonial as an injunction to consider the persisting impact of colonialism on the world around us: to critically engage with how colonialism has shaped the distribution of power and wealth, and continues to determine how relations between the global South and North are framed. In this reading, the post stands for a critical perspective that challenges and subverts colonial ideologies and practices. In this way, postcolonialism has developed into an umbrella term for the study and critical consideration of a whole range of issues, such as racism, nationalism, migration, cultural identity, bodies and performativity, representation, intersectionality, feminisms, knowledge production and many more. The books for which you find reviews on poco.lit. all address different thematic aspects of this vast field of postcolonialism.

Postcolonial discourses are context-specific. Poco.lit. is based in Berlin, Germany. This is a context, where from the 1990s onwards scholars like Encarnación Gutiérrez Rodríguez, Kien Nghi Ha, Maisha-Maureen Auma and others began to explore postcolonial questions and their local ramifications from their Black, feminist and migrant perspectives. In spite of their efforts Postcolonial Studies are still barely institutionally acknowledged and postcolonial literature is only slowly gaining visibility. Often, theoretical and methodological approaches of postcolonial critique are imported from Anglo-American contexts – the linguistic sphere that, arguably, dominates scholarship in this field. This is one of the reasons we choose to run poco.lit. bilingually, in German and English: we want to make relevant English texts accessible to German audiences, and at the same time we want to highlight the postcolonial literature that is developing in Germany and make it accessible to English-speakers. On poco.lit., you can find, for example, a review of Sharon Dodua Otoo’s novella the things, i am thinking while smiling politely, which is something of a classic of Afro-German literature, as well as reviews of more recent publications like Olivia Wenzel’s novel 1000 Serpentinen Angst and Deniz Ohde’s Streulicht.

Postcolonial literatures are always reinventing themselves, and calling on the discourse around them to keep up. It’s a broad field and under its banner, we also discuss post-migrant literature on our platform – an area of representation that sometimes seems particularly relevant to the context in which we find ourselves. As what postcolonial literatures do continues to change, so will our understanding of the postcolonial.